SemiBatch Reactors : mass balance expression

Follow us on Twitter ![]()

Question, remark ? Contact us at contact@myengineeringtools.com

1. SemiBatch reactor

2. Semi Batch reactor perfectly stirred and isotherm : mass balance

3. Stoechiometry and reaction rates

4. Volume Change Considerations

5. Practical Applications and Examples

6. Common Challenges and Solutions

7. Optimization Techniques

8. Example Calculation: Mass Balance in a Semi-Batch Reactor

SemiBatch reactors are often presented in Universities as a very specific case. It turns out they are more common than thought in process industries, as they offer some advantages for example in terms of control of the reaction (add slowly one of the reactant in default to avoid too brutal reactions or to minimize side reactions). This page focusing in applying the general mass balance equations to SemiBatch reactors.

1. SemiBatch reactor

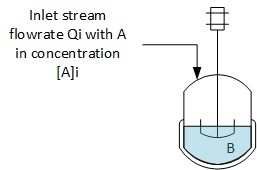

A SemiBatch reactor is basically a batch reactor, but with either one stream in or one stream out.

Both are possible, for the sake of simplicity in the explanation, only the SemiBatch with an inlet of reactant is described here.

The reactants are loaded at the beginning of the process sequence except one of them. When the inlet of material to SemiBatch reactor is opened, the process starts and will stop once whole the reactant to add has been introduced in the reactor. Once the right conversion rate is reached, the reactor is opened and discharged.

The reactor outlet is closed, however the inlet is opened (at least for one of the reactants). The general mass balance equation can then be modified the following way :

Inlet = Outlet + Consumption + Accumulation

Inlet = 0 + Consumption +

Accumulation

The units of each component of the expression is a material flowrate : mol/s for instance.

In the applications below, we consider the case that the SemiBatch reactor considered is :- Perfectly stirred

- Isotherm

2. SemiBatch reactor perfectly stirred and isotherm : mass

balance

As the inlet stream can be any reactant, let's assume for the balance below that the reactant A, in the reaction A + B = C + D is not loaded in the reactor at t = 0, but only B is loaded at 1st.

The fact to have the reactor perfectly stirred also helps in expressing the consumption / production of reactants and products as it can be expressed as the product of the reaction speed by the volume (r'V)

The mass balance for each component will be the following (r' is a consumption speed and r is a formation speed) :Reactive A

FA = 0 + r'A.V + dnA/dt -> Qi.[A]i = r'A.V + dnA/dt

Reactive B

0 = 0 + r'B.V + dnB/dt -> r'B = -1/V * dnB/dt

Product C

0 = 0 - D'C + dnC/dt -> rC =1/V * dnC/dt

Product D

0 = 0 - D'D + dnD/dt -> rD = 1/V * dnD/dt

The system of reaction speed can be expressed the following way :

r'A = (Qi.[A]i - dnA/dt)/V

r'B = -1/V * dnB/dt

rC =1/V * dnC/dt

rD = 1/V * dnD/dt

Top 5 Most

Popular

1. Compressor

Power Calculation

2. Pump Power Calculation

3. Pipe Pressure

Drop Calculation

4. Fluid Velocity in pipes

5. Churchill Correlation

(friction factor)

3. Stoichiometry and Reaction Rates

For the reaction , the stoichiometry tells us that the rates of consumption and formation are related. Typically, for a reaction with stoichiometric coefficients of 1 for all species, the rates are related as follows:

This relationship is essential for solving the system of differential equations that describe the reactor's behavior. It ensures that the mass balances are consistent with the reaction chemistry.

4. Volume Change Considerations

In semi-batch reactors, the volume is not constant if there is a significant inlet flow rate. The volume change can be described by:

This means that the volume is a function of time, and this must be taken into account when solving the mass balance equations, particularly for concentrations which are defined as moles per unit volume.

For example, the concentration of species A in the reactor at any time is given by:

Since changes with time, the derivative terms in the mass balances must account for this change. The accumulation term for species A, for example, would involve both the change in moles of A and the change in volume:

5. Practical Applications and Examples

Semi-batch reactors are widely used in the chemical industry for processes that require careful control of reaction conditions. Some common applications include:

- Polymerization reactions: where monomers are added gradually to control the molecular weight distribution of the polymer.

- Fine chemical synthesis: where precise control over reaction conditions is necessary to maximize yield and selectivity.

- Pharmaceutical manufacturing: where semi-batch operations can help manage exothermic reactions and ensure product quality.

Example: Esterification Reaction

Consider an esterification reaction where an alcohol and an acid react to form an ester and water:

In a semi-batch setup, the alcohol might be charged initially, and the acid is fed slowly to control the reaction exotherm and avoid side reactions like dehydration of the alcohol.

The mass balances for this system would be set up similarly to those described above, with additional considerations for the heat of reaction and temperature control if the reactor is not strictly isothermal.

6. Common Challenges and Solutions

Operating semi-batch reactors comes with its own set of challenges. Here are some common issues and potential solutions:

- Temperature Control: Exothermic reactions can lead to temperature spikes. Solutions include using jackets or coils for cooling, and controlling the feed rate of reactants.

- Mixing Issues: Poor mixing can lead to localized high concentrations and potential hot spots. Using efficient agitation and proper reactor design can mitigate this.

- Volume Management: As the reaction proceeds and more reactant is added, the volume increases, which can affect mixing and heat transfer. Reactor design must account for the maximum expected volume.

- Process Control: Maintaining consistent product quality requires careful control of feed rates, temperature, and mixing. Advanced process control systems can help manage these variables.

7. Optimization Techniques

Optimizing a semi-batch reactor involves maximizing the yield and selectivity of the desired product while minimizing operating costs and ensuring safe operation. Some techniques include:

- Optimal Feed Strategies: Determining the best rate and timing for adding reactants to control reaction rates and selectivity.

- Temperature Profiling: Adjusting the reactor temperature over time to optimize the reaction rate and product distribution.

- In-situ Monitoring: Using analytical tools to monitor the reaction progress in real-time and adjust conditions as needed.

- Model Predictive Control: Using mathematical models of the reaction system to predict the best operating conditions.

8. Example Calculation: Mass Balance in a Semi-Batch Reactor

8.1. Define the Reaction and Reactor Conditions

We consider a reaction:

- Reactor Volume (Initial): V0=100L

- Initial Moles of B: nB0=50mol

- Feed Stream of A:

- Concentration of A in the feed: [A]i=2mol/L

- Volumetric flow rate: Qi=10L/h

- Reaction Rate Constant: Assume a first-order reaction with respect to A and B, with rate constant k=0.05L/(mol\cdotph).

8.2. Initial Conditions and Rate Equations

- Initial volume V0=100L

- Initial moles of B, nB0=50mol

- Initial moles of A, C, D = 0 (assuming no initial A, C, or D)

The reaction rate for a first-order reaction with respect to both A and B is:

But since it's a semi-batch reactor and we're feeding A, the concentration of A and B will change over time.

8.3. Mass Balance Equations

For component A (being fed into the reactor):

For component B (initially charged):

For products C and D (assuming they do not leave the reactor):

8.4. Volume Change Over Time

Since A is being fed into the reactor, the volume changes with time:

Assuming constant density and no volume change due to reaction, the volume at any time t is:

8.5. Solving the Differential Equations

Let's simulate this system over a period of time using numerical integration techniques. For simplicity, we assume first-order kinetics and a constant volume reactor (which may not be entirely accurate but serves as a simplified example).

For simplicity in calculation, let's assume we can approximate the system using small time intervals Δt.

Let's calculate the moles of each species over a 10-hour period using a timestep of 1 hour.

Initialization

- nA,0=0 mol

- nB,0=50 mol

- nC,0=0 mol

- nD,0=0 mol

- V0=100 L

Time Stepping

At each time step t:

- Update the volume:

- Calculate the concentration of A and B:

- Calculate the reaction rate:

- Update the moles of each species based on the mass balance equations:

- Update the moles for the next time step:

| Time (h) | Volume (L) | Moles of A (mol) | Moles of B (mol) | Moles of C (mol) | Moles of D (mol) | Concentration of A (mol/L) | Concentration of B (mol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.500 |

| 1.0 | 110.0 | 19.77 | 49.77 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.180 | 0.452 |

| 2.0 | 120.0 | 39.14 | 49.14 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.326 | 0.409 |

| 3.0 | 130.0 | 58.19 | 48.19 | 1.81 | 1.81 | 0.448 | 0.371 |

| 4.0 | 140.0 | 77.00 | 47.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 0.550 | 0.336 |

| 5.0 | 150.0 | 95.62 | 45.62 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 0.637 | 0.304 |

| 6.0 | 160.0 | 114.11 | 44.11 | 5.89 | 5.89 | 0.713 | 0.276 |

| 7.0 | 170.0 | 132.49 | 42.49 | 7.51 | 7.51 | 0.779 | 0.250 |

| 8.0 | 180.0 | 150.80 | 40.80 | 9.20 | 9.20 | 0.838 | 0.227 |

| 9.0 | 190.0 | 169.08 | 39.08 | 10.92 | 10.92 | 0.890 | 0.206 |

| 10.0 | 200.0 | 187.33 | 37.33 | 12.67 | 12.67 | 0.937 | 0.187 |